Dr Bindeshwar Pathak, the founder of Sulabh International Social Service Organisation, is widely recognized in India – and around the world – for dedicating his life to building a nationwide sanitation movement that transcended borders, spanning over five decades. His lifetime work has made a critical difference to the lives of millions of severely disadvantaged and impoverished, lacking access to basic amenities such as toilets. His work has been groundbreaking in liberating manual scavengers of human waste from their centuries-old, caste-imposed, abominable work, thereby restoring their dignity and human rights

Dr Pathak drew inspiration from Mahatma Gandhi, and his endeavours aligned closely with the principles of the United Nations. Over the past five decades, he has dedicated himself to championing the cause of human rights of manual scavengers of human waste – a large section of Indian society that was historically relegated to the lowest rungs of India’s caste-based system, predominantly women, who have been tasked with cleaning dry latrines and dispose of nightsoil manually.

Dr Pathak’s unwavering commitment involved not only rehabilitating these manual scavengers but also restoring their dignity through new skills development and alternative employment. His actions serve as a compelling example of fostering peace, tolerance, and empowerment through non-violent means

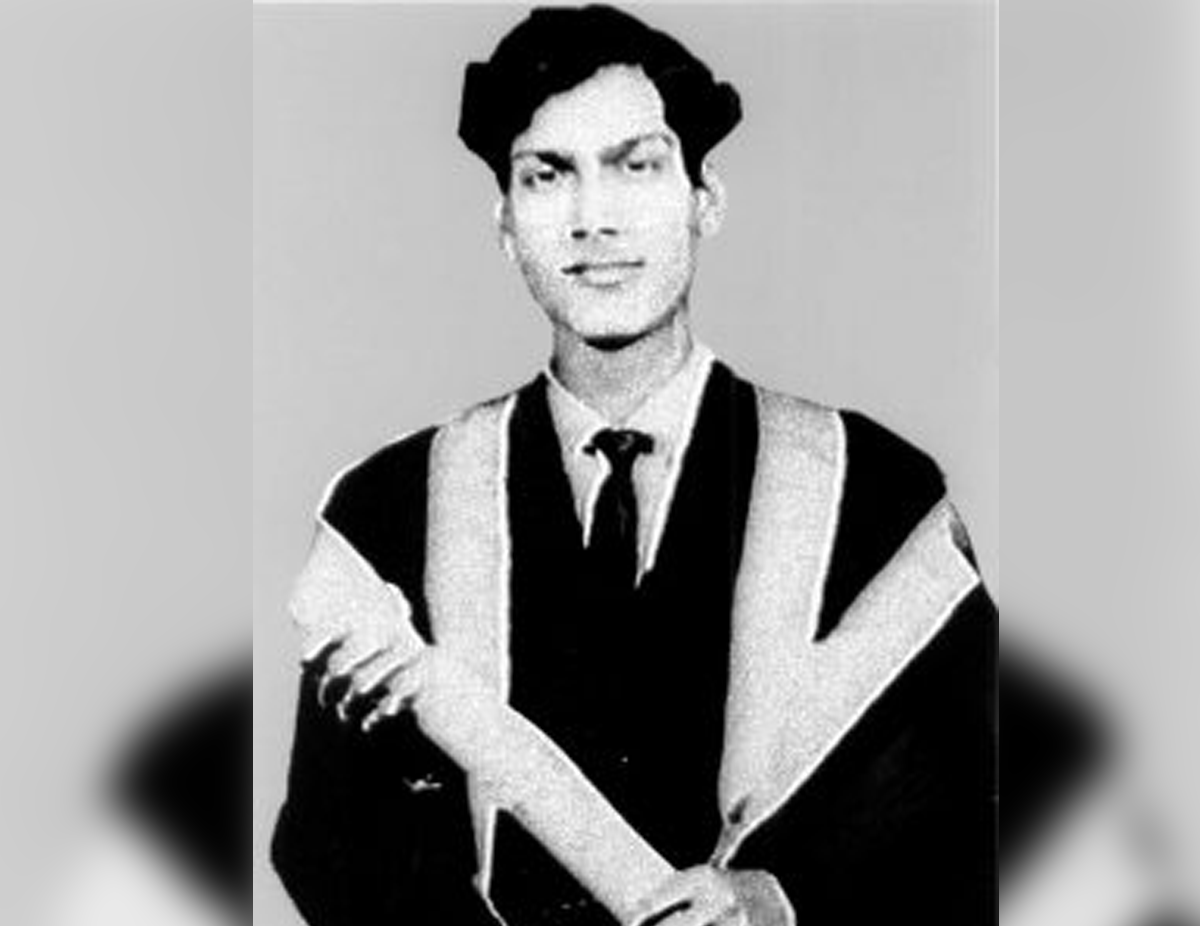

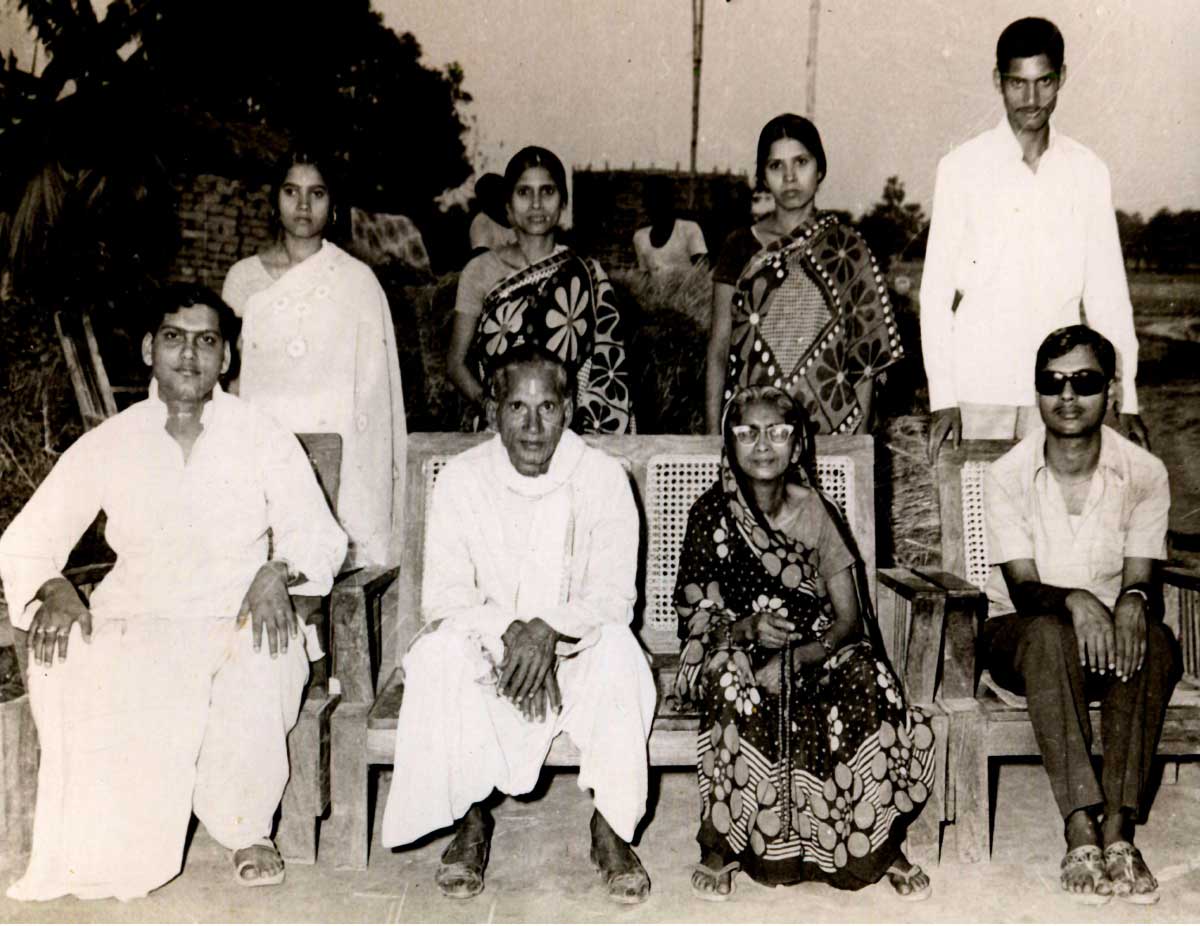

Dr Bindeshwar Pathak was born to a Brahmin family of Rampur Baghel village of district Vaishali, Bihar. His mother, Yogmaya Devi and father, Ramakant Pathak were respected members of the community. Dr Pathak was profoundly influenced by his mother’s belief in altruism. He would often say, “From her, I learned to give without expecting anything in return.” Honesty and integrity were his guiding principles. Sulabh International, the organisation that he founded and built into an institution of worldwide repute, emerged through tenacity embedded in these values.

Pathak spent his childhood and adolescent years in the village where he completed his school education. He later moved to Patna and graduated in sociology from B N College.

After completing his graduation, he worked as a teacher for a while before joining Gandhi Centenary Committee in Patna as a volunteer. This was, however, not his original plan. He wanted to study master’s in criminology from Sagar University in Madhya Pradesh. While travelling to Sagar, however, he was persuaded into giving up his journey and the plan by two gentlemen, his close acquaintances, to join Gandhi Centenary Committee.

They assured him that he would be paid well. Hard-pressed for money, Pathak agreed to abide by their advice. However, when he approached the office of the Committee, he learnt that there was no such job as he was told. On offer was an opportunity to work as a volunteer, instead.

Since he had anyway missed the deadline for admission at Sagar University, he decided to accept the offer.

Later in his life, over a period, he could complete his advanced education to the level of D Lit, got married, and had children while Sulabh grew in its size and reach across the country.

While working for Bihar Gandhi Centenary Committee, Pathak was asked by the general secretary of the organization, Saryu Prasad, to focus on the restoration of human rights and dignity for untouchables. He was subsequently dispatched to a town called Betiah. “I had my initiation with Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy while working for this organization. Gandhi strongly advocated cleanliness and was an ardent advocate of the rights and dignity of the harijans (the nomenclature assigned at that time to the socially oppressed), especially the manual scavengers. He longed for a solution that could replace dry latrines. I was extremely inspired by his cause which was further strengthened by his own life experiences”, Pathak shared.

As a child, Pathak had often noticed his grandmother treating the woman from the community of ‘untouchables’ with discrimination. Considering her impure, she would sprinkle the house with water from the river Ganges, after she left, in a bid to purify it. One day, out of curiosity, Pathak touched the woman while his grandmother noticed. The consequences that followed were severe: he was made to swallow, by force, cow dung and urine, bathed in freezing Ganges water on a wintry morning to cleanse and purify him. This illustrates the level of superstition and discrimination that prevailed against untouchables in the India of those times.

His childhood memories came alive when he was in Betiah, Bihar. Here, he witnessed the magnitude of the problem more closely: the community of manual scavengers – as they were considered untouchables – was brutally treated and almost condemned to live an inhuman life. One incident, in particular, left a lasting impression on his mind.

Pathak recounted, “One day, while working there, I witnessed a harrowing incident: a bull attacking a boy who wore a red shirt. When people rushed to save him, somebody yelled that he was an ‘untouchable’. The crowd instantly abandoned him, leaving him to die.” He adds, “This tragic and unjust incident shook my conscience to the core. On that day, I vowed to fulfil the dreams of Mahatma Gandh to fight for the rights of the untouchables and also to champion the cause of human dignity and equality in my country and around the world. This became my mission.”

In the year 1968, troubled by the pathetic conditions faced by the untouchables and motivated by Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy and teachings, Pathak invented a technology to replace dry latrines and do away with the need to clean them manually. It had the potential to ultimately put an end to the practice of cleaning manually the bucket toilets, which were in use in the country, by the members of untouchable communities in the country.

“My idea was not just to provide a solution but also to liberate the society that remained imprisoned in formulaic traditions. I was determined to restore the dignity of manual scavengers, (which) they were deprived of”, says Dr Pathak.

He adds, “For these women, their freedom, voice, and basic human rights were forfeited the moment they were born, as they were perceived to belong to the lowest stratum of India’s caste-based society. By virtue of their birth, they worked as manual scavengers, cleaning dry latrines and facing severe social discrimination. I resolved to free manual scavengers from the shackles of modern-day slavery and dedicated my life to this cause. I invented a sustainable technology known as two-pit pour-flush toilet, which could replace the bucket toilets requiring manual scavengers to clean them and eventually bring an end to this inhuman practice.”

Pathak was convinced that to liberate manual scavengers from their inhuman occupation, every household had to have a proper toilet. In those days, in Indian villages, most households simply didn’t have a toilet. Those that did were equipped with dry latrines, which had to be manually cleaned by the “untouchables.”

Open defecation was a common phenomenon, and women were the worst sufferers. They had to go out for defecation in the cover of darkness – early morning or after sunset – thus running a very high risk of exposure to crime, snake bites, and even attacks from other animals. The lack of toilets exposed children to diarrhoeal diseases, and many died before reaching the age of five. The concept of public toilets was non-existent.

Despite the significant social challenges, Pathak’s project was initially a non-starter and got entangled in red tape. However, Pathak remained undeterred.

“I was in need of funds, so I sold a piece of land in my village, my wife’s ornaments, and even borrowed money from friends to run the organization. This period of my life was very difficult,” Pathak recalled.

“At times, I even contemplated suicide. Since I had no money, I slept on railway platforms and often skipped meals. For a long time, there was no sight of any work. I was going through a miserable phase and was on the verge of a breakdown.”

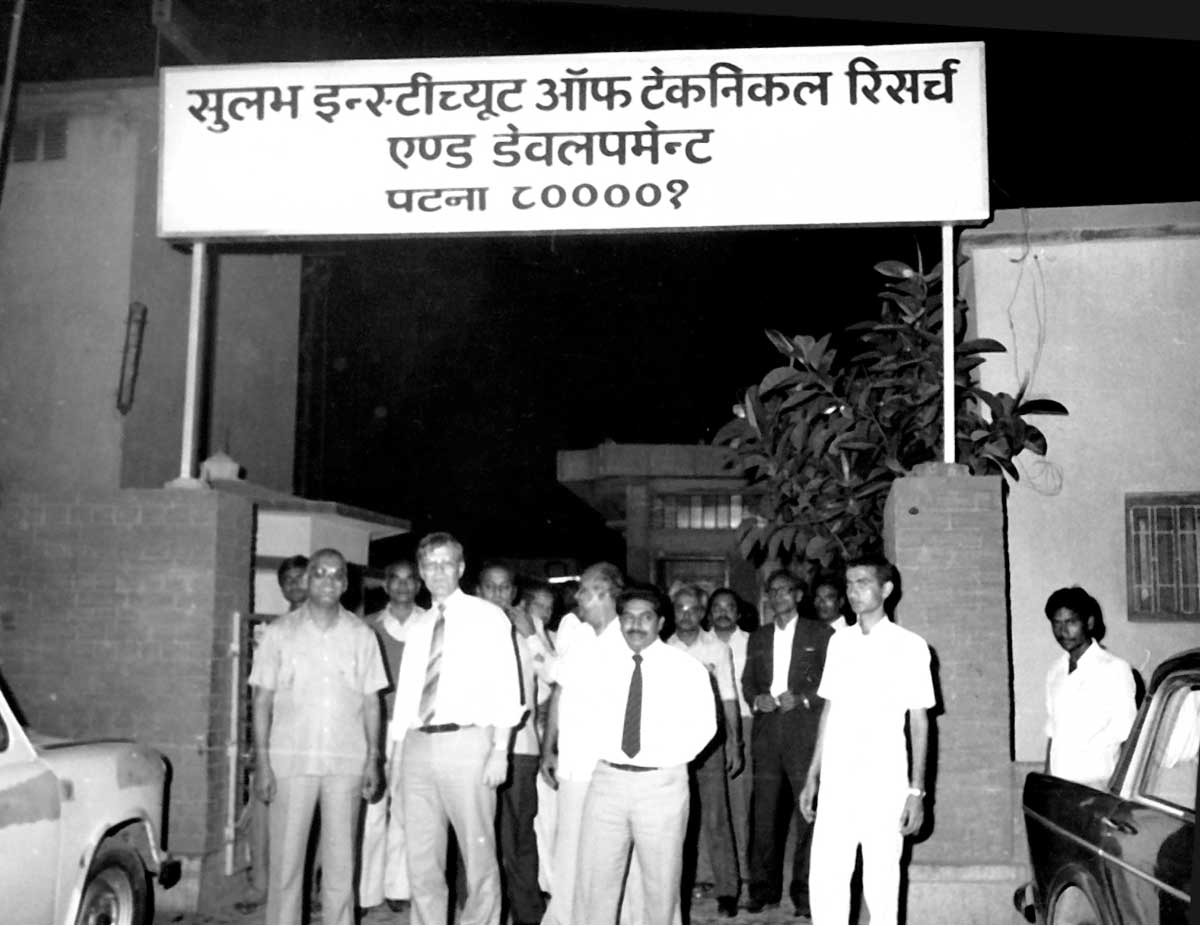

However, during this phase of his struggle, Pathak received an important piece of advice: in 1971, a civil servant who had reviewed Pathak’s file, pending government approval for funds, was impressed by his noble cause and the massive impact it was likely to create in resolving India’s sanitation problems. He advised that instead of asking for grants Sulabh should charge for implementing projects, and from the savings run the organization. This way, the organization would be sustainable, making it more attractive to be awarded government contracts.

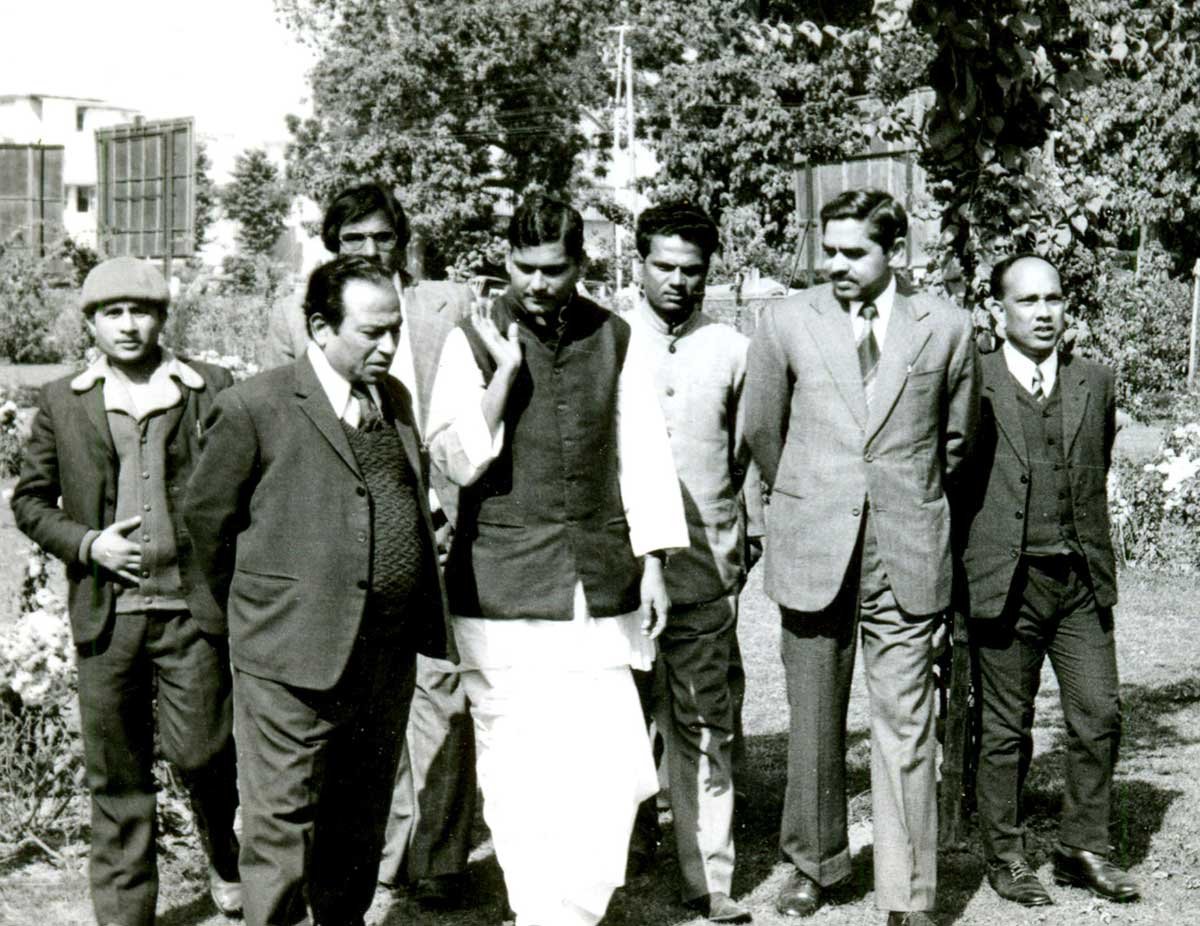

In 1973, Pathak persuaded a member of the Bihar Legislative Assembly (MLA) to write a letter to the then Prime Minister of India, Mrs. Indira Gandhi, addressing the situation and liberation of scavengers. The letter requested her to personally attend to the problem. Within a fortnight, he received a reply from Mrs. Gandhi, stating that she had written to the Chief Minister, urging him to give personal attention to this matter.

While the government acknowledged Mrs. Gandhi’s letter and initiated action, the issue once again became entangled in the cobweb of bureaucracy, resulting in a stalemate.

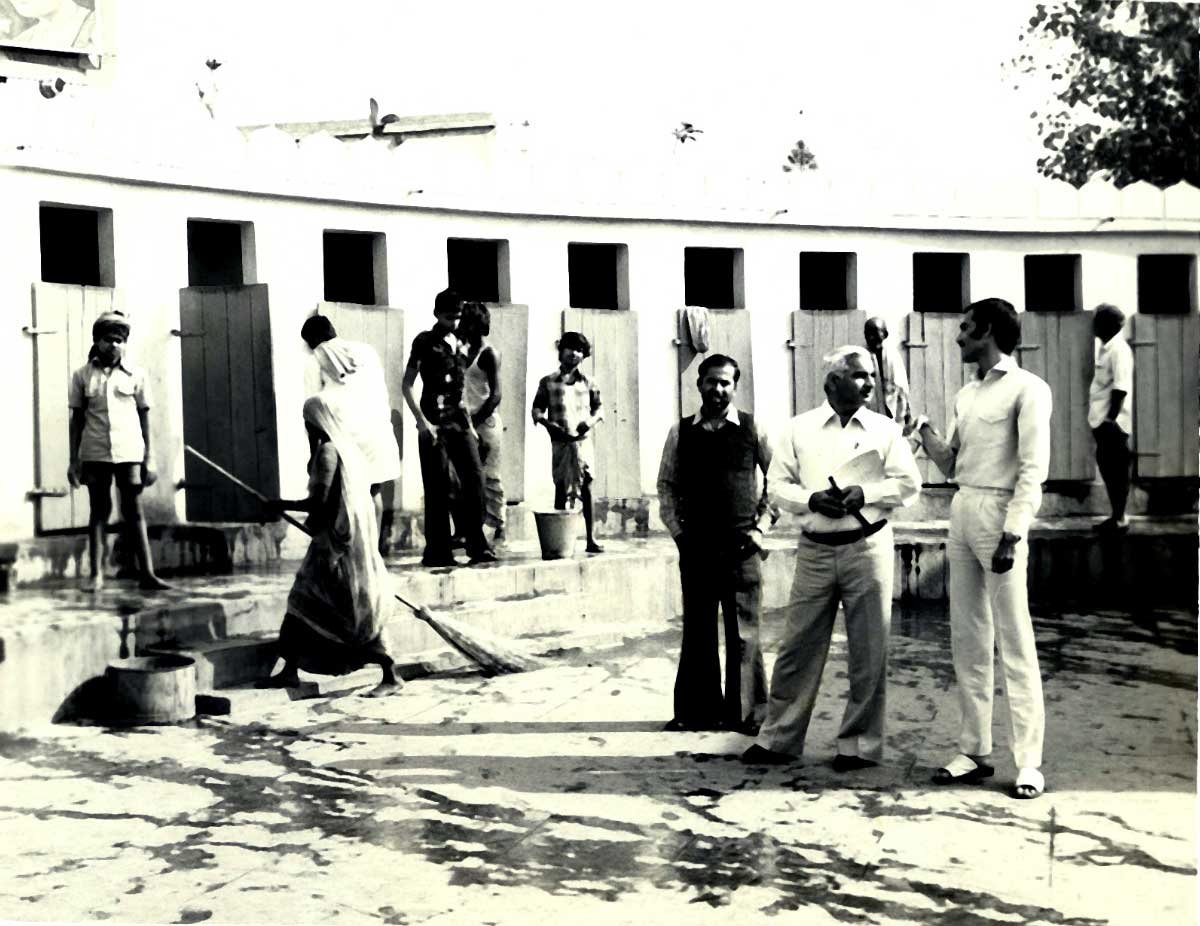

However, the turning point for Pathak occurred in 1973, when an officer of the Arrah municipality, a small town in Bihar, provided him with 500 rupees to construct two toilets for a demonstration on its premises. The impressive toilets garnered the approval of authorities, leading to the sanctioning of a project for broader implementation.

Pathak dedicated himself to the cause, going door-to-door to motivate and educate beneficiaries to convert their bucket latrines into Sulabh toilets. The programme proved to be a resounding success, prompting invitations for Pathak to replicate it in Buxar, another town in Bihar. Within a year, Sulabh was operational in the state capital, Patna.

In 1974, the Bihar Government issued a circular to all local bodies, urging them to enlist the assistance of Sulabh in transforming bucket toilets into Sulabh two-pit-pour-flush toilets, a design conceptualized, researched and developed by Pathak. The primary objective was to alleviate scavengers from the dehumanizing task of manually cleaning human excreta and transporting it as a head-load. The program was subsequently implemented throughout the state of Bihar.

During the same year, Pathak introduced the novel concept of maintaining public toilets on a pay-and-use basis, which was a pioneering initiative in India. This idea quickly gained popularity nationwide. By 1980, in Patna alone, 25,000 individuals were utilizing Sulabh’s public facilities. The success of the program garnered attention from both national and international press.

In 1980, The New York Times praised Dr Pathak’s mission, describing him as an “articulate advocate of the role of voluntary organizations in development.” The article went on to state, “The major reason for success has been Pathak’s sociological and psychological genius – he knows how to translate ideas into action and motivate people to act.” Similarly, in 1985, The Washington Post characterized Pathak’s mission as “formidable”.

The Sulabh Sanitation Movement went beyond the realm of just sanitation; it was a campaign framed around human rights within the context of sanitation. Dr Pathak was resolute in his commitment to challenge the discriminatory social structures that barred manual scavengers from entering temples.

In 1988, Pathak took a groundbreaking initiative by leading a group of manual scavengers, accompanied by Brahmins, to the Nathdwara temples for rites and rituals. Initially met with resistance and denial of entry, Pathak opted for a persuasive approach instead of a confrontational one. Through his efforts, he successfully convinced the priests to allow them entry, marking a historic turning point.

This unprecedented action brought Pathak widespread acclaim, resulting in him and the group received an audience with the then President Venkataraman, Vice-President Dr Shankar Dayal Sharma, and the Prime Minister.

The then-Indian Prime Minister, Mr Rajiv Gandhi commented,

“Unless these things are achieved India cannot be said to be going on the road to development.”

In 1991, Dr Pathak was honoured with the Padma Bhushan for his monumental efforts in liberating and rehabilitating manual scavengers, as well as for his contribution to preventing environmental pollution through the implementation of pour-flush toilet technology, which served as an alternative to dry latrines.

Shortly after that in 1992, Pathak was bestowed with The International Saint Francis Prize for the Environment – Canticle of All Creatures by Pope John Paul II. The jury in a statement that Pathak was unanimously chosen for his “comprehensive and interdependent nature of Pathak’s environmental and social commitment to the human responsibility of the earth.”

Over the years, Pathak’s initiatives have significantly impacted the traditional practice of inheriting inhuman occupations based on caste. Through his visionary leadership, he provided crucial support and inspiration to marginalized manual scavengers, particularly in the towns of Alwar and Tonk. Pathak’s efforts involved the rehabilitation of former manual scavengers, equipping them with skills in beauty, food processing, sewing, embroidery, and even personality development courses.

These initiatives played a pivotal role in their economic empowerment, fostering self-reliance and enabling them to live with dignity in society. Additionally, Pathak established a school and vocational training centre in New Delhi, offering quality education to former manual scavengers and their children.

Pathak’s sanitation movement has played a crucial role in reshaping societal attitudes towards health, equality, dignity, and the rights of women and girls.

In 2012, Dr Pathak embarked on a significant philanthropic mission following a directive from the Supreme Court of India. The court took note of the inadequate efforts by the state government and its agencies to alleviate the suffering of the widows of Vrindavan. This came after the National Legal Services Authority charity filed a Public Interest Litigation petition seeking to improve the living conditions of these widows.

The charity informed the Court about the deplorable conditions in the government shelters of Vrindavan, highlighting that when a widow passed away, her body was often dismembered and disposed of due to a lack of funds for proper funeral rites. In response, the court assigned Sulabh International the responsibility of enhancing services and care for these vulnerable women.

Dr Pathak promptly took action to assist them. “When I first relocated to Vrindavan [in 2012] to witness the conditions of the widows firsthand, I was horrified to discover their heart-wrenching plight,” says Bindeshwar Pathak. “It was inhuman and a stain on our culture and civilization.”

Pathak initiated the effort by providing a monthly stipend of 2,000 rupees ($30) to each of the widows in Vrindavan. “Money offers the widows much-needed security, and by directly giving it to them instead of officials running the shelters, we ensure they have control over their funds, allowing them to spend it as they see fit,” he explains.

Sulabh also offers ambulances, free weekly health checkups, and training programs to teach women new skills, including reading and writing, embroidery, and candle making.

Since 2013, Pathak has been leading the widows in an annual celebration of the Indian festival of colours, Holi, defying old customs that still, to this day, prevent most widows in India from participating in festivals or wearing coloured attire, not to talk about their being denied participation in family functions, or remarrying. His act of rebellion sparked a nationwide debate on discarding rigid traditions that deprive widows of the opportunities enjoyed by other women in India.

“The neglect of widows living in Vrindavan is a problem specific to certain families and communities,” says Pathak, who is also advocating for government legislation for the protection, welfare, and maintenance of widows. “It stems from moral deprivation and the greed of specific families. However, times are changing, and we must instil in the new generation the importance of caring for its elders.”

Pathak championed the need for toilets in schools. Today, in many parts of India, the attendance of female students has remarkably improved due to the availability of toilets, but more needs to be done. Under his leadership, Sulabh International has played an instrumental role in realizing Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s vision to make India a clean country. Recognizing these efforts, Sulabh was awarded the Gandhi Peace Prize for implementing the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (Clean India Campaign).

In the words of Mahatma Gandhi’s grandson, Professor Rajmohan Gandhi,

“I am the son of the son of Mahatma Gandhi but Dr Bindeshwar Pathak is the son of his soul. If we were to go to meet M.K. Gandhi, he would first greet DrPathak for the noble work that he is doing and then meet me.”

Pathak’s humanistic actions have transformed the lives of thousands of men, women, and children in India, enabling them to lead lives of dignity. Pathak emphasized, “God helps people to help others. Change in society is possible if we ourselves become the agents of change. We require the collective action of everyone to reform the unjust practices in our society.”